For this week’s writing I decided to look back on an essay which I wrote in May 2021 for a theory final. The brief essay is a look at the first few cues of Elmer Bernstein’s score to Ghostbusters. An analysis of the score finds that the composer, though following inciting action on-screen, chose to invest somewhat heavily in common tropes of horror composition rather than comedy, his musical specialty. The result is a score which expertly blends supernatural action with the lighthearted comedy Ghostbusters is known for.

The essay has been slightly edited from its original academic prose into something more accessible to normal people, as far as that’s possible. I refer to pitches by their number on a tone clock, which is a simple 12-point circle used to organize pitches regardless of register. A tone clock is a mod 12 system where 0 = C, 1 = C#, and so on. I’ve added translations for readers who aren’t familiar. I’ve also included timestamps for the video “"Ghostbusters - FIRST 10 MINUTES” pasted below. For the analysis I used Timothy Rodier’s gorgeous reproduction of the original film cues — check out his website Omni Music for more great film scores. Cheers and happy Halloween!

Putting the Ghost in Ghostbusters

The score to the 1984 film Ghostbusters — written by Elmer Bernstein and orchestrated by Peter Bernstein and David Spear — represents an early use of synthesizers and post-tonal compositional technique in comedy film music. Unlike prior synth-heavy scores like John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) and Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), or largely post-tonal scores such as John Williams’ Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), the score to Ghostbusters would use synthesizers in tandem with an incredible 110 piece orchestra in a variety of tonal languages.

In an essay accompanying the 2019 release of the complete score to Ghostbusters, Peter Bernstein outlines the unique demands of the Ghostbusters score: “The ghost story had to sound scary, but not so scary that the comedy, which might be happening at the same time, was overshadowed. Meanwhile, both the ghost story and the comedy had to coexist with the love story, and all of this with the end of the world in the offing.” Elmer Bernstein’s approach to telling three-stories-in-one is a marriage of the macabre and the melodic through extensive use of whole tone scales established early in the score, and which change from cue to cue based on the demands of the action on screen. This essay will analyze the initial “ghost theme” and track its development and alterations throughout the early cues of the score.

The film begins as most films do with cue 1M1, which opens with a cantation by the ondes martenot, a 72-key oscillating tube electronic keyboard related to the theremin, capable of long pitch quavers. The quavering effect of the instrument, used extensively by 20th century French composer Olivier Messiaen, is occasionally associated with Sci-fi. (It was used in film scores such as the 1962 Laurence of Arabia, Mars Attacks!, Dr Who and the Daleks, and There Will Be Blood. In recent years, Radiohead's Kid A pushed the ondes into the public eye.) The cantation, shown in Figure 1, outlines pitch 3 (Eb) as something of a tonal center, rising to it twice before simmering back down on pitches 0 (C) and E (B). This is an early example of reliance on pitch material from whole tone scale 1 (WT1), a symmetrical scale encompassing the pitches 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and E (C#, D#, F, G, A). Using WT1 is a clever way to obscure any tonal center for these supernatural themes, as it removes leading tones while remaining ethereal in character. It allows the music to be approachable but ambiguous, safely riding that line of “scary, but not so scary”.

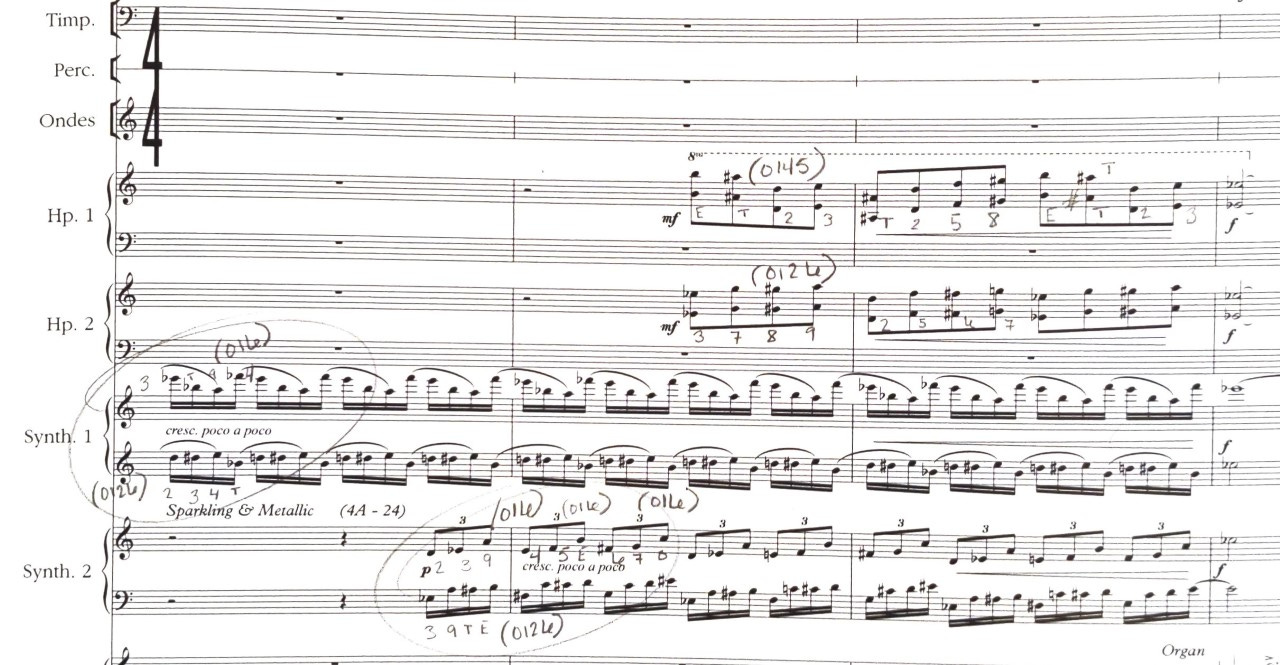

An establishing shot on the Library Exterior — the interior of which serves as the setting of the first scene in the film — is accompanied by a building cacophony of synthesizer sounds and harp (Figure 2). The tone color of this accompaniment is bright — Synth 2 contains the in-score annotation “Sparkling & Metallic”. The overall effect of these bars (0:19-0:32) is dizzying, as pitch material and rhythmic variance are heavily contrasted between voices, but there is logic to the madness.

On a macro level, this is an effectively orchestrated crescendo. On a micro, it is a neat smoke & mirrors trick. With Synth 1 beginning on beat 1 of measure 5 with sixteenth note ascending runs once-removed from the downbeat (creating a sort of hemiola) Bernstein obscures any sense of traditional time. When Synth 2 begins on beat 4 of measure 5, with the right hand playing eighth note triplets, the three binary lines against one ternary create even more distortion. The final addition of Harps 1 and 2 beginning on beat 3 of measure 6 in on-beat eighth note ascending runs should provide a stable frame from which the listener might hear static beats, especially with the aid of the triplet figure played by Synth 2, but this is not the effect. By this point, strict time has been subverted, leading to an opening G7(#5) chord played by all the winds and strings in the orchestra (this resolves in the next beat to a 2nd inversion F7 chord). The almost-full entrance of the orchestra coincides with a visual fade-in on a lion statue in-film, one of the famous library lions from the New York Public Library. Pitch material within this section varies, but Figure 2 shows prime forms of binary and ternary are established either as (0126) or (016), respectively, indicating that Bernstein did not pick this dizzying aural display at random.

Rather than form a tonal center for these establishing bars, or choose pitches at random, Bernstein systematically creates atmosphere through disciplined use of rhythmic and harmonic organization.

That the pitch material remains ambiguous as film material cuts in and out of logos and establishing shots is worth noting, as it is not until a visual cut to the Librarian, the first human shown on-screen, that film-watchers will hear the first stable theme (Figure 3, :037-0:52). This theme, also played by the ondes martenot, this time in octaves with violin and cello, utilizes more of WT1, and is rhythmically more strict than the previous material from Figure 1. This theme forms the basis of most melodic material heard whenever supernatural action takes place on-screen, so I will very cleverly call it the “supernatural theme”.

The next time we hear material which references this supernatural character is in 1M4, when the film’s heroes investigate the basement of the library (8:25) — the setting of the inciting action of the film. The overall mood of 1M4 is decidedly sporadic, as scenes between 1M1 and 1M4 establish some elements of comedy, a departure from the strictly supernatural character which dominated 1M1.

1M4 begins with the indication “Slyly (♩ = 72 )”, and pizzicato strings trading off with bassoon, clarinet, horn, xylophone, harp and celesta hits. This section is tonal, beginning in Eb Major (enharmonically respelled as D# in the score), then embarks along an ascending 5-6 diatonic sequence. At measure 6 of this cue, the contrabass and ondes martenot strike an E (B♮), and Synth 1 plays a melody comprised of WT1 material, and the augmented pitch 6 (F#), shown in Figure 4. This pitch augmentation from 5 (F♮) could be understood to arise from the B minor center which the Ascending 5-6 sequence had previously worked up to. Bernstein keeps it ambiguous while again ensuring the theme is approachable, utilizing the pitches E (B♮) and 9 (A♮) to envelope the F# within the previously established indicator of supernatural action, WT1. The contour of the line calls back to the original ondes cantation from Figure 1, which centered similarly on Eb as Figure 4 does on F#.

The Synth 1 melody coincides with a shift of camera perspective, an attempt to subvert visual and audio material simultaneously in order to build suspense. This comes as the heroes traverse the labyrinth of books in search of a ghost, which could be lurking around any corner as far as the film-viewer is aware. The score returns to the pizzicato string character by measure 10 with a cut back to a stack of vertical books, this time in Ascending 5ths leading to a Grand Pause, timed with an on-screen joke about the books. After the G.P. comes a great example of one of Bernstein’s anti-stingers (9:03), a two-note piano turn after Ray whispers, “listen! Do you smell something?”

The pizzicato section continues for two more bars before leading to a new on-screen situation where the heroes discover ectoplasmic residue. The accompanying annotation within the score is marked “Syrupy”, and the strings are written to glissando utilizing the pitches outlined in Figure 5 and 6. Each instrument reaches upward to replace the starting pitch of the instrument above it, creating motion without moving anywhere tonally. Bernstein excels at this kind of atmospheric setting-material, marrying the effects of the score with the context of the film, as with Figure 4.

Utilizing non-tonal material like this allows Bernstein to insert his score into the fundamental threads of the film without having to create action or movement toward one specific climactic moment. In this way, Bernstein’s score becomes integral to the consumption of the film. This collaborative integration was intentionally sought by both Elmer Bernstein and the director of the film, Ivan Reitman, as Peter Bernstein writes: “[Elmer] called it one of his most difficult projects to find the right tone for, and he was constantly on the phone with Ivan discussing scene by scene just how far to take the comedy or the drama . . . he used to describe film composing as a "collaborative art," and Ghostbusters turned out to be a very good example of it.” 3

Violin 1: 3 → 6 (+3) | Violin 2: T → 3 (+5) | Viola: 7 → T (+3) (Figure 6)

Later in the film we meet Dana, a supporting character to the heroes’ action, and love interest to Peter Venkman. In measure 13 of cue 3M1 the film-viewer sees Dana exit a taxi and walk across the street to her apartment. Bernstein lines this up with a solo cello melody which derives influence from the primary supernatural theme, shown in Figure 7. This theme utilizes some more stepwise motion than previous themes, and is accompanied by a very tonal background. Moments of chromaticism and leaps from WT1 pitches give it a slightly foreboding color as Dana enters her apartment.

Later in cue 3M4, we see Dana unpacking groceries on-screen as supernatural events start to occur. Her egg carton starts shaking, the eggs pop and cook in their shells, and her refrigerator begins to glow as growls come from within. As it happens, Bernstein utilizes the ondes martenot and three synthesizers. First, the ondes ascends three octaves from C#2 (1) to Eb4 (3), clearly within the confines of the WT1 relationship. After a gong hit, the three synthesizers begin quavering between the ascending pitches G and A (7-9), descending pitches Bb and Ab (T-8), and ascending pitches B and C# (E-1), entering in the order mentioned, shown in Figure 8. Curious here is Bernstein’s organization of ascending versus descending whole tone quavers, where ascending quavering pitches are derived from WT1, and descending from WT0, creating a very unpleasant dichotomy of sound while eggs explode on-screen. This contrast to the pleasant, lightly chromaticized “Dana’s theme” heard in 3M1 is striking.

The use of whole tone scalar language by Elmer Bernstein is both decisive and helpful in the achievement of his compositional goal, which was to marry the three distinct elements of story present in Ghostbusters. Further examples within the film are plenty, especially as the film reaches its narrative height with cataclysmic events, biblical story elements, possessions, and other horror tropes. The decision to pivot the score around horror tropes, versus comedic or romantic tropes, would set this score apart from others within Bernstein’s comedy wheelhouse such as Animal House (1978) or Airplane (1980). It would also stand as one of the largest and most varied orchestras Bernstein would write for in his career as a film composer. There’s no doubt that this score stands as a worthy if unexpected example of accessible horror writing in film music for its incredible orchestration, tonal language, and effective thematic development.