Rush Limbaugh's Cousin is Saving Western Music

Stephen Limbaugh III has recently emerged as the musical darling of the new right.

Want to feel old? It’s been three years since the cells in Rush Limbaugh’s lungs choked out his last gasp for breath. Nearly an entire presidency without his wit, his grace, or that papercut smile. But like a phoenix from the ashes, a new Limbaugh is on the rise: Stephen Limbaugh III—a man who calls himself the “world’s greatest pianist”, and Rush’s first cousin once removed. Stephen’s views verge on extreme, but they haven’t stopped the music industry, in lock-step with right-wing think-tanks like the Claremont Institute, from investing in his bizarre ascent toward musical legitimacy. Far from an exceptionally gifted artist or capable thinker, young Limbaugh’s main asset is his name—something he wears with red white and blue pants, and a towering ego to rival America's Anchorman.

If you don’t follow many music professors, you might have missed the minor controversy that kicked Limbaugh into the recent spotlight. Responding to news that the Iceland Symphony had hired Canadian conductor and coloratura soprano Barbara Hannigan as chief conductor, Limbaugh commented: “The woman here has just been named the new conductor for the Iceland Symphony. Here she is performing ‘music’ by Ligeti…” followed by a 2015 clip of the musician singing a difficult excerpt of György Ligeti’s anti-opera, Le grande macabe.

The post drew predictable flak for its misogynist tone and stale taste, amplified by the revelation that Stephen is related to Rush—an apple discovered very close to the tree. To a lot of classical listeners, Ligeti represents the first coherent entry into a forward looking “classical tradition” after the radical cultural shifts of the early 20th century. Stephen, meanwhile, chooses to make a name for himself as classical music’s RETVRN guy, bringing the shit-eating arrogance of “my kid could paint that!” to the usually liberal classical industry.

Following the time-honored playbook of the American reactionary, Limbaugh can’t help but tell on himself, revealing the dull machinations of a mind that couldn’t begin to engage in the art of the moment. It’s no surprise that Le grande macabe, a product of hundreds of years of musical development, would seem like low hanging fruit to a pianist whose retirement plan is to ape an AM radio host.

But a deeper look reveals a more complex figure—a man who’s found success riding out the family name, and the more troubling connections that come with a career in reactionary media. More than mere shitposter, Limbaugh is using his background to carry the torch of the new right into the world of music.

Meet Stephen Limbaugh III

Stephen Limbaugh III’s musicological origination is this: at the age of 11, a troubled Limbaugh started playing the piano, quickly becoming obsessed with classical music. He dropped out of high school during his junior year to focus on music full-time, splitting his days between piano and classical trumpet with the St. Louis youth symphony.

According to Stephen, Rush was instrumental throughout these early years, encouraging the young pianist and comforting his worried parents. It’s likely Rush chipped in to help pay for lessons and schooling, if his bizarre gift rituals are any indication: “[During Christmas], Rush himself would commandeer a room in his brother David’s house and stack up boxes on boxes of Apple products. One by one, we were invited in to pick out what we wanted. He loved sharing his passions with other people.”

After this, Stephen presumably studied keyboard and composition at University of Missouri-Kansas City conservatory. Here he complained that professors encouraged him to explore writing something other than triads, a basic building block of harmony dating back to J.S. Bach.

At 21, Limbaugh packed up and moved to Los Angeles where he played keyboard in Kingsley, a now defunct Alt Rock group that logged two national tours, an MTV appearance, and a “most promising band of the year” award. Here he got his first taste of the big time as Kingsley signed a record deal and found themselves opening for bands like Hoobastank.

Years passed as Limbaugh found work as a studio musician, punctuated with the occasional interview heralding him as the millennial Mozart. He took every opportunity to build his image as classical music’s conservative bad-boy: “I go to church on Sundays, do a Bible study on Mondays, and have lots [of] cocktails with friends Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. I love fireball shots, like a total bro. I swear, that shit is the new Jager.”

A gig playing for an HBO executive led to engagements playing Emmy and Golden Globe parties. As his star rose, so too did his lofty ambitions: “I plan on being the most viewed/subscribed pianist on YouTube.” This is around the time Limbaugh became wise to his brand. The Limbaugh name, associated with a type of proud nationalism thanks to Rush, found itself plastered on Stephen’s shirts, tank tops, and piano. American flag pants—his greatest marketing schtick—emerged as the pianists’ preferred stage wear.

This penchant for colorful pants plays into his distinctly individual approach to performance—an attempt at the revival of the superstar as a sort of musical sommelier, where the performer is entrepreneur first, musician second. “[I’m] like Liberace meets Johnny Knoxville,” he said in an interview with Agents of Innovation, a pro-capitalist podcast celebrating American entrepreneurs. Limbaugh identifies heavily with this ethos, placing himself in the tradition of Franz Liszt, Paderewski, Liberace, and Elton John, all while calling himself the “greatest pianist in the world.”

The approach paid off in 2015, when Limbaugh’s first album, Pants, debuted at #16 on Billboard before peaking at #12 as the only ranked album by an independent artist at the time. It likewise charted as the top contemporary classical piece, encouraging the composer to return to the simple embrace of classical music as an outlet for his shifting ambitions, which now included Hollywood movie scoring.

The following year, Limbaugh would score the first of many right-wing documentaries in Dinesh D'Souza’s Hillary’s America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party, which won four razzies. He would follow this with Scooter Downey and Jon du Toit’s Hoaxed starring alt-right nationalist Mike Cernovich, nationalist Amanda Milius’ The Plot Against the President, as well as Death of a Nation, another film by Dinesh D’Souza featuring white nationalist Richard Spencer. Limbaugh also clocked credit for musical work with PragerU, the right-wing media organization infamous for funneling impressionable youth to the alt-right.

In 2018, Limbaugh booked a number of high profile political gigs—including an appearance at Turning Point USA’s 2018 Student Action Summit, where his red white and blues were on full display. Here he shared the stage as a pianist and speaker with esteemed figures like Ron DeSantis, Tucker Carlson, Charlie Kirk, Candace Owens, Jordan Peterson, Donald Trump Jr., Brad Parscale, Dan Crenshaw, Kyle Kashuv, Alex Epstein, and Morton Klein, among others. Weeks after, he would be the featured guest at a White House Christmas party, trading his American flag pants for a more respectable suit and tie.

Limbaugh’s personality can best be gleamed from a 2020 thread titled “Stephen Limbaugh”, in which he claims to have cracked songwriter Max Martin’s “melodic math”, a basic set of principles the hit writer uses to write pop songs. “I am entering my fourth year as a film composer, though my musical interests go much beyond this medium, not the least of which are dank memes,” Limbaugh opens.

“Eventually, I will share my research that has unlocked Max Martin’s ‘melodic math.’ I am 80% through a unified theorem that if applied in earnest, will allow any novice to compose melodies like Max Martin, John Williams, or Stephen Sondheim, all without the assistance of artificial intelligence, while allowing for great artistic latitude. The written formula, which will be completed by year’s end, in its current form is hidden in a briefcase underneath my bookshelf.”

It takes a bold man to claim to have developed an entirely new musical analysis, especially for a pianist with no experience in theory research. Imagine Johnny Depp announcing that he’s developed a new type of film analysis, Miguel Sanó coming up with a new system of baseball analytics. Limbaugh takes his claims pretty far, asserting that his theory would be “universally applicable”, to all music, whether it’s opera, EDM, nursery rhyme, or film score.

Shockingly the thread goes dead a few months later, with still no word from Limbaugh on what came of the hidden briefcase. It seems he’s since laid down his lofty ambitions to pay the bills, appearing in a number of promo videos for the Vienna Symphonic Library, a software developer specializing in orchestral samples based in Vienna.

An overview of Limbaugh’s career reveals a set of puzzle pieces that together form the picture of a real boy. Without his baked-in connections to figures in conservative and right-wing media, we see an emerging musician taking a predictable path—say yes to every gig, dazzle nonmusicians with technical skill, and take every opportunity to get your name out in the world. Yet this baked-in path verges farther to the right of Rush’s Reaganite hysterics, spilling beyond domestic partisan drama onto the ideological battlefield of western values. Here is not just a nepo baby making good use of his connections, but forging new ones, promoting the principles of the new right through classical music.

Young Heretics

Stephen Limbaugh didn’t set out to be the champion of western music, but there’s little doubt he’s finding his voice. The pianist has appeared in numerous interviews throughout the past five years with an increasingly reactionary message. In a 2020 discussion on Capitalism in Music with Spencer Klavan of the Young Heretics podcast, for example, Stephen offers classical western tropes like simple triads and “positive cultural appropriation” as artistic qualities to strive for, and return to.

Listeners hoping for a scholarly chat on the intersection of economics and aesthetics might want to skip this one. Limbaugh—a conservatory-trained player piano—knows little about music history, and Klavan even less. Thankfully for Limbaugh, he’s in good intellectual company. His host is a prolific culture writer, having authored pieces like Video Games: The Last Refuge of Manhood, Should Conservatives Watch Violent Movies? and our favorite, Dr. Seuss and the Culture of Fear.

Their discussion revolves around Limbaugh’s thesis that the technological developments of the gilded age1 were responsible for expanding the orchestra and creating the conditions which allowed romantic music to flourish. As advancements like valves led to wind instruments which could play chromatic scales, composers were able to slowly experiment with these new developments while working within a set of rigid aesthetic values (Limbaugh’s biggest concern seems to be triads) which were enshrined by the masters of the late 18th century.

The story goes that capitalism, then, was the liberatory force behind the romantic era of music (coincidentally some of Limbaugh’s favorite), but that somewhere along the way we lost the gentle creep of free-market progress—turning instead to the logical madness of serialism and the musical avant-garde.

Like his Ligeti post, Limbaugh’s thesis betrays a lack of insight. In worshiping the incidental products of a certain era of productive positivism, what he calls “freedom”, he ignores that positivism became a rule itself. If you must “push the rules” in order to succeed—as it was in the romantic era—then the rules really exist as a mechanism for cultural profit first, and a framework for art second. Artistic boundaries become binary, where the innovators rise to the top in search of money, honor, and glory, and the stationary become failures forgotten by history.

Under Limbaugh’s own framework, innovation was doomed to burn out as the gimmicks wore off and the challenge of advancement grew exponentially. Those same market forces have shown us that you can only force so many bizarre new instruments onto the stage. Once orchestration and tonality had been stretched to their breaking points—as they had by composers like Mahler, Debussy, Strauss, Sibelius—the only innovations left were outside of the rigid classical values which held the whole thing up. Tonality was first on the chopping block with Schoenberg, but soon came rhythm, orchestration, structure, then the very concept of music itself. This is the music Limbaugh despises, a product of the system he celebrates.

This is not because classical music has abandoned the “freedom of the market”, but because it has adopted the market into its very soul. Composition is competition to adopt the prerequisites of musical progress in a long race to the top. Schoenberg’s developments in total chromaticism weren’t any more revolutionary than Berlioz’ developments in orchestration 100 years earlier. They are simply evolutions of an aesthetic system obsessed with invention.

Asked to recommend a “must listen”, Limbaugh racks his brain before offering Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker. To Limbaugh, this represents the confluence of a Russian societal awakening and that idea of “positive cultural appropriation”—an example of nationalism and the capitalist mindset come to life. Yet for as much as this is true, The Nutcracker is the antithesis of whatever sensibilities Limbaugh thinks he has; its nationalist kitsch and brief parallel harmonies are engaging for a flash in history before the quest for progress renders it novelty. Worse yet, it’s become market novelty in our time—trotted out once a year by every orchestra and ballet company as easy ticket revenue necessary to stay afloat in a market economy which, if actually allowed to play out, would render orchestral music obsolete. No more Nutcracker.

This is what happens when music becomes an ideological cudgel—you end up a sad, confused sloganeer with incoherent opinions that contradict your values. The ultimate twist here is Limbaugh convincing himself to follow this path—not for his art, but because it’s his best bet at building a career. His Mike Cernovich scoring gigs, White House parties, and Claremont Institute interviews are all thanks to the name. In trying to live up to Limbaugh, he throws away his objectivity in the same pursuit of capital responsible for the art he urges us to reject. It’s a lot of work to just be boring.

The Claremont Connection

Young Heretics host Spencer Klavan and the Claremont Institute are worth a quick aside, as they put Limbaugh’s incoherent rhetoric into context. The Claremont Institute is a big-moneyed nationalist think-tank—if you can imagine—founded in 1979 on the principles of natural rights and limited government. The non-profit’s primary function is to sponsor young conservatives through its fellowship program, which it finances with both private and public funds. In 2020 the think-tank took home $398,265 in forgiven PPP loans, according to their 2021 Form 990.

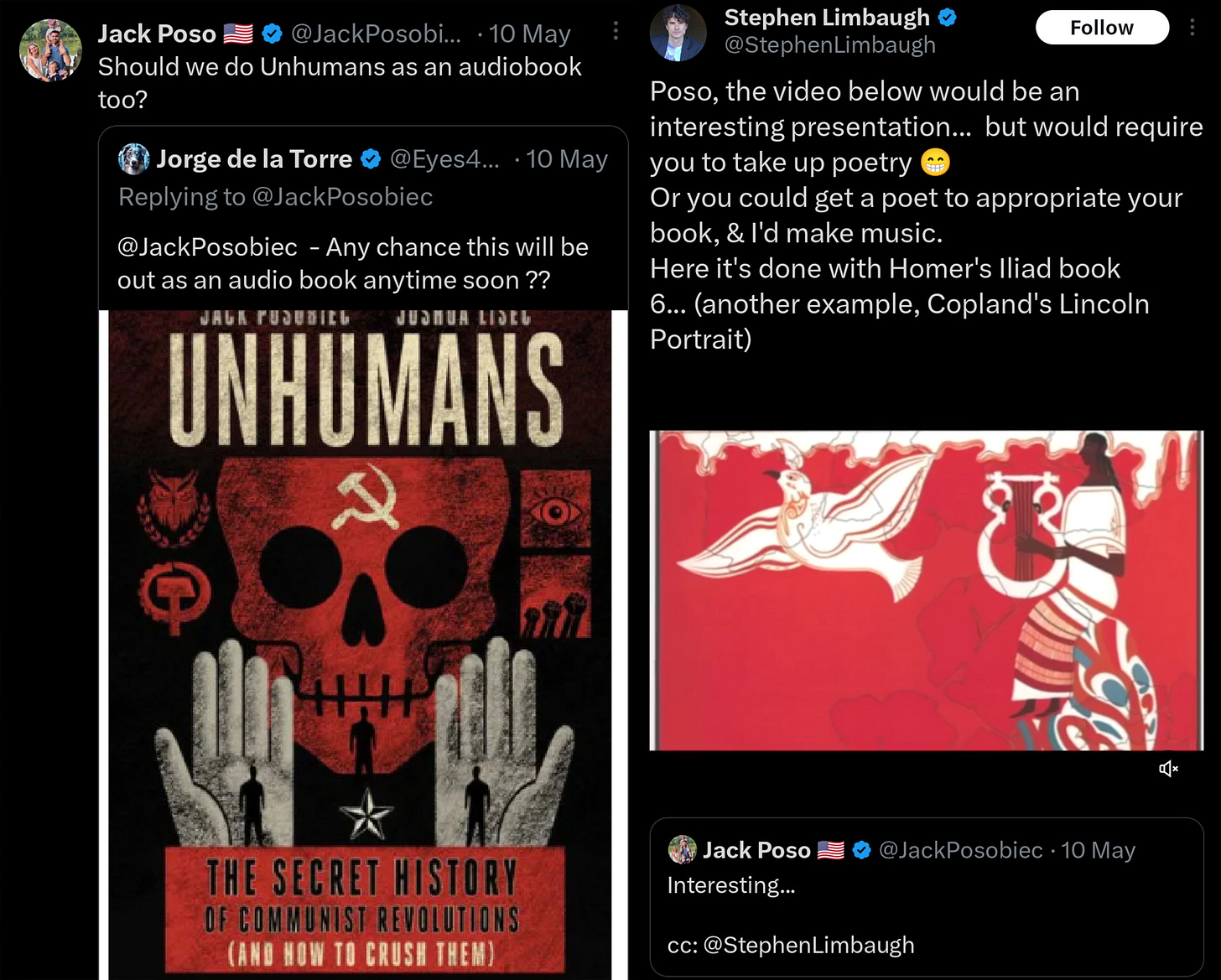

Reactionary pseudo-intellectuals Ben Shapiro, Jack Posobiec, Laura Ingraham, Jack Murphy, Charlie Kirk, and Charles C. Johnson have all held fellowships with the Institute, along with countless other figures in law, media, and legislation. All right-of-center ideologies are represented, from rabid NatSec war dogs to pro-life Federalist Society freaks and champions of the far-right. Joining the ranks in 2022 was Stephen Limbaugh as Claremont Institute Lincoln fellow.

In addition to Spencer Klavan, the Claremont Institute employs prominent right-wing figures such as United States Agency for Global Media CEO Michael Pack, Society for American Civic Renewal members Scott Yenor and Ryan Williams, Jon Pollard defender and intelligence bureaucrat Angelo Codevilla, NatSec hawk and Victor Orban lobbyist David Reaboi, as well as John Eastman and Christopher Caldwell, who need no qualifiers.

With three exceptions—including Clarence Thomas’ ideological tutor John Marini—each Claremont Institute executive draws a six figure salary. In 2023, the Institute reported total executive compensation of just under $1 million, with an additional $3.1 million paid out in other salaries and wages. Together, these compensations account for 40% of the non-profit’s total expenses.

Though the Institute maintains some PR respectability as a conservative nationalist think-tank (rather than an explicitly authoritarian one), its history is nonetheless riddled with ties to less subtle organizations. In March 2024, for example, the Claremont Institute came under flak for its involvement in the Society for American Civic Renewal (SACR), a male-only fraternal order centered on extremist notions of white, Christian authoritarianism. Reporting by the Guardian exposed numerous Claremont Institute employees as brothers of SACR, such as President Ryan Williams and executive Scott Yenor, in addition to former Claremont Institute fellows such as Nathan Fischer, president of the SACR chapter in Dallas.

The ties run deeper than dual membership, however, as the Claremont Institute collaborated as a direct financial and logistical supporter of the SACR from its beginning. A trove of internal documents reveals the Institute provided SACR leaders advice as they applied for 501(c)10 status, and sponsored the budding extremist group to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars. Mired in secrecy, the SACR’s only public officer is the Charles Haywood, who shares personal connections with Yenor and Williams. Haywood serves as SACR president out of his compound in Caramel, Indiana, where he envisions serving as a “warlord” who could recruit soldiers to assist in the coming struggle to topple the U.S. government and implement an authoritarian regime.

This is the company with whom Limbaugh finds himself—far-right knuckle draggers and grifters, sure, but also accomplished policy advocates and media personalities who earn lifetimes of wealth in the pursuit of an even more reactionary system of governance. Rather than distance himself from them, Limbaugh chooses to share stages with them, appear on their podcasts, and use their followings to boost his own. His aesthetic opinions are best understood in this context: the product of musical careerism in a space where nationalism and tradition come before all. Unfortunately for Limbaugh, music makes a poor vessel for ideology.

Pledging Allegiance to Steve

There’s a lot to say about Limbaugh’s politics and ideology, and a lot to talk about with regards to the way he represents a certain type of toxic nepotism. But somewhere, a very annoying voice is shouting an all-too familiar refrain: Sure, Stephen Limbaugh is the cryptofascist cousin of one of American radio’s worst stars, and sure, he’s comically narcissistic, and sure, he’s a repeated collaborator of conspiracy theorist and convicted fraud Dinesh D’Souza, and sure, this is too many commas for one sentence, but what about the music, man? It doesn’t matter how annoying he is if his music is good! And so I feel the profound duty to talk a little about Limbaugh’s work—specifically, how bad it is.

Let’s start here with his two flagship works (no pun intended): not only has Limbaugh arranged his own version of The Star-Spangled Banner, but he’s set The Pledge of Allegiance to song as well. These two works act as something of a Rosetta Stone for Limbaugh’s ideology and how it reflects in his work.

His setting of The Pledge represents a perfect window into both Limbaugh’s aesthetic goals and how he’s become so mystifyingly successful. Limbaugh’s setting and orchestration occupies a very dated kind of Adult Contemporary cheese, with shimmering orchestration supporting a simplistic, quarter note piano pulse straight out of the soft rock charts of yesteryear and the vocalist adopting his best breathy Christian Rock tone.

I’m an atheist who was raised in a secular household, but I grew up around evangelical Christians, and I’ve developed an anthropological fascination with evangelical media. It’s a wildly insular space, so cut off from the rest of American culture that its attempts to copy it feel alien and deformed, but nonetheless well-funded and carefully produced. Even if Limbaugh weren’t a true believer, it makes good business sense to pander to both the cultural whims of the Protestant Right as well as their aesthetic ones.

Indeed, unlike other far-right media dropouts like Ben Shapiro or Matt Walsh—two men whose careers in the grifting space were initiated by failing to fail upward in mainstream Hollywood—Limbaugh seems at least mostly content to stick to preaching to the choir (though he has a habit of bitterly complaining about Hollywood’s supposed rejection of him on X, née Twitter.) So while I, as someone who didn’t grow up listening to Christian Rock, might recoil from this setting, it’s a canny and shrewd way of pandering to a less-than-discerning audience.

Indeed, this setting of The Pledge is perfectly representative of a specific brand of faux neo-romanticism popular amongst right-wing musicians who like to complain about where classical music went wrong. To a seasoned listener, this setting doesn’t really sound like anything from any part of the classical canon, but it isn’t supposed to. Limbaugh’s clearly aiming for part of the same audience as musicians like Ludovico Einaudi or André Rieu—close enough to the aesthetics of classical music to fool an audience drawn to the cultural cachet of the genre, but apathetic enough toward the music to avoid the challenge of the real stuff.

This too gives the grift away. I’m far from the first to point this out, but tonal music is still very popular in the contemporary classical music world. If you look through a list of classical works which won the Pulitzer Prize in the last two decades or so, you’ll find more tonal winners than not—from minimalists and post-minimalists like Adamses John and John Luther, to the bold vocal work of Caroline Shaw, to the more freewheeling tonal idioms of Julia Wolfe.

Even Krzysztof Penderecki—among the most famous modernist composers of his era and the backbone of most of the horror movies you’ve ever seen—spent the last several decades of his life writing distinctly neo-romantic music, such as his stellar Seventh Symphony, Seven Gates of Jerusalem. But even modern tonal works are often viewed as too adventurous and experimental to a certain subset of the classical music world, if for no other reason than none of these works sound like the tonal music of the past.

Penderecki’s neo-romantic music was still forward-thinking: he never abandoned the formal and timbral languages he pioneered in the 1960s and 1970s, and those eerie and distinctly modern ideas are all over Seven Gates. John Adams is a minimalist, a post-modern genre with little connection to the rigid aesthetic laws of the Common Practice Era. John Luther Adams, Caroline Shaw, and Julia Wolfe all flirt to varying degrees with post-minimalism, a looser and more timbrally adventurous descendant of the aesthetic pioneered by Adams, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, and others.

The ideology of the musical reactionary is that it simply isn’t enough to find new ways to express tonal ideas. To them, all art stopped being good sometime in the early 20th Century, and we all must return to the Eurocentric standard of the mid-19th Century, if not earlier. It isn’t even necessarily atonality that musical reactionaries oppose: it’s any sort of newness.

But, of course, most audiences—even particularly reactionary ones—don’t really want a carbon copy of the German Exclusive Canon. After all, why listen to a composer who sounds just like Beethoven when we have unlimited access to the real Beethoven’s entire catalog? It’s a hard sell. So the Reactionary Composer tends to work in the realm of the pop-classical hybrids of the late 20th Century. It’s almost tragic: the Reactionary Composer lives in an in-between hellworld, upholding so-called masterworks of the past without ever having the freedom to sound like them.

Intent aside, it’s also important to note that the music fucking sucks. Limbaugh’s setting of the Pledge of Allegiance not only sounds like a rejected Bryan Adams single from 1992, its melody is also far too upbeat and jaunty to express the kind of breathless, teary-eyed devotion to nationalism he wants it to. Speed the melody up ten clicks or so and play it on a steel drum, and it sounds like the whitest Calypso single of 1957.

His arrangement of The Star-Spangled Banner, meanwhile, expresses a different flavor of pop-classical aesthetic: the film score. Given Limbaugh’s ambitions for Hollywood glory, it makes sense, as does his choice to arrange the National Anthem to begin with. Setting The Pledge of Allegiance immediately signals a very specific type of patriotism, one that can make you a lot of money under the right circumstances, but not one that will garner you any mainstream attention.

The National Anthem, however, is a useful enough song with an established history in the more mainstream corners of the classical music industry to be a potential ticket to more widespread attention. Aside from Limbaugh’s bizarre warmongering additions to the text (which he claims were part of the original setting), this arrangement is at least a classier affair than his Pledge of Allegiance.

But it, too, is dated. An arrangement like this would have played a little better in the 1990s or early 2000s, when this type of orchestral aesthetic was more common. Unfortunately for Limbaugh, film music hasn’t sounded like this for a while.

Like many reactionary figures in the arts, Stephen Limbaugh’s commitment to a return to tradition is exactly what holds him back from more mainstream attention. Even reactionary audiences aren’t really all that amenable to the kind of traditionalism they pretend to protect, because traditionalism, by its nature, is old-fashioned. And old-fashioned music isn’t really familiar to an audience whose idea of a film score is built on a dozen Hans Zimmer acolytes and their underpaid staff.

With so many seeds starting to sprout, it’ll be worth watching where Limbaugh takes his career. While his bark is still much worse than his bite, Limbaugh’s shown he has the very real potential to dupe less than scrupulous industry leaders into welcoming him onto programs and piano benches across the nation, along with all he stands for. After all, these are the music fans who sold out Walt Disney Concert Hall to see Dennis Prager conduct Haydn. Stephen should know—he led the standing ovation.

Limbaugh and Klavan refer to this era the belle époque, the rules-based period of frivolous arts investment for the robber baron class between 1871-1914.

Hi Aidan, I'm a former Portlander, studied with Tom Svoboda, and glad you wrote this piece. But bashing Tchaikovsky doesn't help your case. If you or I could write three bars as good as this master we'd be immortal. I'm a professional classical musician who has played many a Nutcracker (complete ballet) and am sad that in my current hometown of St. Louis, the forces of "capitalism" apparently no longer allow for live performances of this magnificent masterpiece. You can however hear our recording for RCA on Spotify. All the best.